The Coronavirus: Asking Parents to Keep Children at Home. Is it the Right Balance?

According to the NSW Department of Health the Novel coronavirus 2019 (2019 n-CoV) was identified in China during a respiratory illness outbreak in Wuhan which started in late 2019. It causes severe respiratory illness.

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses. Some cause illness in humans, and others cause illness in animals such as bats, camels, and civets. Human coronaviruses cause mild illness such as the common cold. In rare circumstances, animal coronaviruses can evolve to infect and spread (zoonotic) to and among humans. The Novel (new) coronavirus (2019 n-CoV) is a strain of coronavirus that had not been previously identified in humans.

Human to human transmission of the Novel (new) coronavirus (2019n-CoV) is most likely to be through direct contact with infectious patients, by respiratory droplets and via contaminated objects and surfaces (fomites).

Sometimes, animal zoonotic coronaviruses can cause serious diseases in humans such as the severe pneumonia that was often a symptom of the 2002 SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) pandemic.

In 2002/2003 schools around the country were placed on ‘high alert’ to look out for SARS-like symptoms in any students travelling from Asia and China in particular. According to the World Health Organisation, more than 8,000 people became ill with SARS during that period and of those, 774 people died — a rate of 9.6 per cent. Many of the Independent Schools Associations released new SARS pandemic policy guidelines at that time and schools were quick to upload these and develop policies for anyone who was diagnosed with the disease.

Government Advice and Action

Schools in most jurisdictions are allowed to exclude students who have a contagious disease or exclude students who are not vaccinated against a contagious disease that has been brought into the school.

In response to the outbreak of 2019 n-CoV, the Federal Government originally advised that students who had returned from China and were healthy should be allowed to attend school but that students who had been in contact with somebody with coronavirus should stay home from school for two weeks.

However, within a few days, according to The Guardian, in a reversal of its previous advice, the Federal Government toughened its quarantine policy and is now advising education departments and universities to update their policies.

Current advice (at time of publication) from the federal Department of Health is that any student (or staff member) returning from mainland China (not including Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan) who was in, or transited through, mainland China on or after Saturday 1 February 2020 must be isolated at home and should not attend school until 14 days after they were last in mainland China. This does not apply retrospectively, applying only to students who were in mainland China on or after 1 February 2020.

Other students or staff should be isolated at home for 14 days:

- following the last exposure to any confirmed novel coronavirus case; or

- after leaving Hubei Province.

There is no requirement for a child or staff member to be quarantined if they have travelled from other provinces of mainland China (and have not been in Hubei province) and who arrived prior to 1 February 2020, or students and staff who have only been to Hong Kong, Macau or Taiwan.

If the child is diagnosed with the 2019-nCoV they must not attend school or childcare until they are cleared by public health authorities.

This advice applies to schools and early childhood centres.

In Western Australia and in New South Wales, the state governments had earlier imposed a 14-day quarantine period on all Chinese students attending government schools if they have been to China during the vacation break. WA Education Minister Sue Ellery said that the government would continue to follow the advice of the health department. “We continue today, and we will going forward, follow the advice of the Department of Health. We noted the announcement made by New South Wales,” she said. “We are asking West Australian parents to cooperate with us to ensure that if their child has travelled to China, they keep that child at home, away from school for a 14-day period.” Ms Ellery said the request only extended to children who had been to China or Hong Kong in the past 14 days, not those whose parents had.

Schools, therefore, had been given government authority to go further (than the standard exclusion practice in relation to contagious diseases referred to above) and exclude students who may be carrying the Novel coronavirus due to geographical proximity and a greater risk of being in contact with a carrier.

The Federal Government has also introduced travel restrictions in response to the coronavirus outbreak. The restrictions deny entry into Australia for people who have left or transited through mainland China from 1 February. This is reported to have affected about 4050 secondary students. They are also requiring students and families returning from the Wuhan area to be housed at the Christmas Island Detention Centre for a period of time before being allowed to return to Australia

What Are Schools Doing?

It has been reported, in many media outlets including The Australian, the Herald Sun and WA Today, that some non-government schools across Australia are segregating Chinese students and banning pupils from attending class without a medical certificate, if they have recently visited any part of China. Other independent schools are emailing parents with a similar request – with some asking for medical checks before a child’s return to school.

The Herald Sun reported that Federal Education Minister Dan Tehan slammed schools for isolating students and giving parents the wrong advice about how to deal with the risk of the coronavirus outbreak. “Individual schools make their own decisions but the advice from the Australian government is to follow our medical advice”… “Obviously in the end they will have to answer to their parents, but also, they will have to answer to state and territory governments, who have responsibility for schools.”

Confusion and Uncertainty

What we have is the Federal Government originally saying that schools can make their own decisions “but must answer to their parents”. This earlier advice was that healthy students, even if they had returned from China, should be allowed to attend school. Then, three days later, it changed its policy, asking people who have been in Hubei Province to stay at home for 14 days unless seeking medical advice.

We have state governments declaring that all government school students who have been in China, even if they have had no contact with the coronavirus, should not come to school for two weeks and we have individual and systemic non-government schools following a similar approach with some asking for medical certificates and others sending out a blanket ban.

Right now, these mixed messages surely must be causing confusion for our overseas students from China who would like to return to school in Australia. The Guardian summarised this sentiment in their article “Australian students get conflicting advice about return to school”. Given that there are just over 12,000 school-age students from China enrolled in Australia, this may be a huge financial risk!

What Approach Should Schools Be Taking?

What we have learned from governmental responses to this particular epidemic is that expecting certainty of policy may not be reasonable. Information about the epidemiology of a particular virus: how it is transmitted, the length of the incubation period, how long before symptoms are visible, how quickly it is spreading, its seriousness, access to vaccines or cures, may all take a while to determine. Policy is made based on the best information at the time, and must be prepared to change if further information comes to hand which justifies changing the original policy.

Due to the fast-moving nature of the situation and the shifting government advice, schools have been given some leeway as to how they choose to balance protecting the interests of the larger group with the rights and interests of individuals.

One matter seems to be clear. A school’s duty of care to all of its students should be the number one priority. By taking steps to exclude students potentially impacted by the Novel coronavirus, the school is making the priority the greater good of their student body as a whole. This is arguably ineluctable. It does however adversely affect those excluded individuals to whom the school also owes a duty of care.

Schools can take steps to ameliorate the adverse effects on the individuals by communicating with them as clearly and supportively as possible and by offering to support the excluded students with remote learning opportunities during the exclusion period.

Schools also need to be wary of any form of xenophobic or racist behaviour that may be directed towards Chinese (or other Asian) students on their return to school. Whether that be now, for those who have not been in China, or in a week or two after they have met individual jurisdictional or school quarantine requirements.

This matter was raised in The Conversation recently:

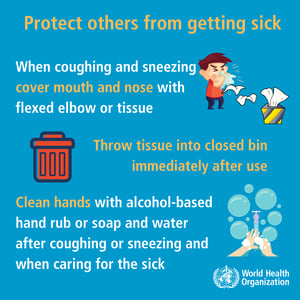

Instead of excluding Chinese students, [where departmental advice does not require quarantine] schools can build trust by actively providing clear information about the rationale for control measures. They can encourage students to take protective actions such as practising good hand hygiene and seeking medical advice by telephone in cases of illness. Teachers can provide students with reliable information.

Ultimately, each non-government school needs to develop its own policies and processes regarding any type of national or international health issue. However, as a matter of risk management, the most sustainable position for a school would be to rely on the latest advice from their state/ territory health and education departments to determine policy and procedures. It would be reasonable to assume that Chief Medical Officers would have access to medical opinion and research on both the disease and quarantining, which an individual school would not. Following departmental guidance should also make it easier to explain to parents and students the measures the school has taken.

Ultimately, each non-government school needs to develop its own policies and processes regarding any type of national or international health issue. However, as a matter of risk management, the most sustainable position for a school would be to rely on the latest advice from their state/ territory health and education departments to determine policy and procedures. It would be reasonable to assume that Chief Medical Officers would have access to medical opinion and research on both the disease and quarantining, which an individual school would not. Following departmental guidance should also make it easier to explain to parents and students the measures the school has taken.

Above all, any policy or procedure must find the best balance between the best interests of the students who have possibly been affected by this virus and those who have not had contact.

Authors

Craig D’cruz

With 37 years of educational experience, Craig D’cruz is the National Education Lead at CompliSpace. Craig provides direction on education matters including new products, program/module content and training. Previously Craig held the roles of Industrial Officer at the Association of Independent Schools of WA, he was the Principal of a K-12 non-government school, Deputy Principal of a systemic non-government school and he has had teaching and leadership experience in both the independent and Catholic school sectors. Craig currently sits on the board of a large non-government school and is a regular presenter on behalf of CompliSpace and other educational bodies on issues relating to school governance, school culture and leadership.

With 37 years of educational experience, Craig D’cruz is the National Education Lead at CompliSpace. Craig provides direction on education matters including new products, program/module content and training. Previously Craig held the roles of Industrial Officer at the Association of Independent Schools of WA, he was the Principal of a K-12 non-government school, Deputy Principal of a systemic non-government school and he has had teaching and leadership experience in both the independent and Catholic school sectors. Craig currently sits on the board of a large non-government school and is a regular presenter on behalf of CompliSpace and other educational bodies on issues relating to school governance, school culture and leadership.

Svetlana Pozydajew

Svetlana is a Senior Consultant at CompliSpace. She has over 20 years of experience in strategic and operational human resource management, occupational health and safety, and design and implementation of policies and change management programs. She has held national people management responsibility positions in the public and private sectors. Svetlana holds a LLB, Masters in Management (MBA), Master of Arts in Journalism, and a Certificate in Governance for not-for-profits.

Svetlana is a Senior Consultant at CompliSpace. She has over 20 years of experience in strategic and operational human resource management, occupational health and safety, and design and implementation of policies and change management programs. She has held national people management responsibility positions in the public and private sectors. Svetlana holds a LLB, Masters in Management (MBA), Master of Arts in Journalism, and a Certificate in Governance for not-for-profits.

About the Author

.png)

Ideagen CompliSpace

Resources you may like

Article

Managing psychosocial hazards in schools: a legal and practical guide for school leaders

School leaders are becoming increasingly aware that workplace safety isn’t just about physical...

Read MoreArticle

Cyber security and AI in schools: emerging risks and governance imperatives

In an era where artificial intelligence (AI) tools are becoming as commonplace as calculators once...

Read MoreArticle

Under 16 social media 'ban’: an explainer for schools

The Australian Government passed a new law called the Online Safety Amendment (Social Media Minimum...

Read More