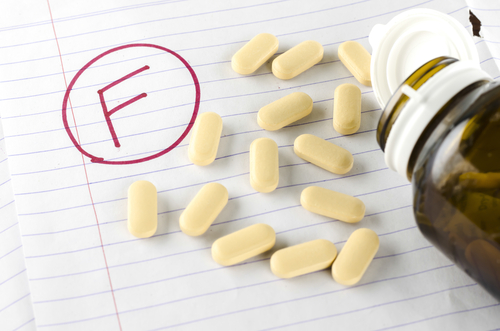

A recent case in South Australia where a private school student escaped jail despite pleading guilty to dealing drugs to fellow students demonstrates the complex issue of how to discipline students who are involved in drug offences.

When a school student is implicated in drug offences they can face consequences under both criminal law and school disciplinary procedures. The difficult question many schools face is how severe their punishment should be, especially when particular circumstances are involved, such as if a student is in their final years of school.

The facts

As reported by the Adelaide Advertiser, a private school student avoided jail after pleading guilty to the trafficking of dangerous illicit substances at two different schools in South Australia. The student was in possession of 22 ecstasy tablets, 17 blue ethylene tablets, almost $3,000 in cash and two electronic scales when he was arrested by police. While the court initially handed down a sentence of three years and two months in jail, with a non-parole period of one year and eight months, this was reduced to a $1,000 three-year good behaviour bond on the condition that the student endeavour to live a drug free life.

The judge viewed the student’s ‘privileged’ life as a factor weighing in favour of punishment, particularly as his parents had provided him with all the opportunities to pursue a quality education. Nonetheless, the principles of sentencing under the Young Offenders Act 1993 (SA) dictate that a prison sentence must not be imposed on young offenders unless the youth is a repeat offender and the Court is satisfied that a prison sentence is the only sentencing option due to the gravity and circumstances of the offence. This is under the premise that young offenders should be rehabilitated through targeted drug-prevention treatment as opposed to being shamed and punished by the criminal justice system.

School responses to drug and alcohol incidents

As evidenced by the Young Offenders Act 1993 (SA), the criminal justice system is evidently opposed to punishing first time offenders – alternatively prioritising lighter sentencing procedures including police cautions, warnings and conferences. This, however, stands in contrast with government policies which state that suspension is to occur immediately after students are caught in possession of illegal substances or caught assisting other students to obtain and/or supply illegal substances.

In incidents involving illicit drugs, the initial actions and responses of the school should focus on the safety and welfare of the students involved. Under legislation specific to each state and territory, schools are required to notify police should they come into possession of an illicit substance. For example, in Victoria, Section 5 of the Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Act 1981 (Vic) states that schools are legally obliged to notify police if they are aware of any possession and/or distribution of illicit drugs.

Separately, internal procedures and actions should also be taken according to the school’s own disciplinary policies.

Oftentimes, however, such disciplinary policies prioritise suspension or expulsion in order to protect the school community. While it is important to protect other students from the influence of convicted drug offenders, the school should also take into consideration the importance of allowing young offenders an opportunity to change their behaviour in a safe and controlled environment.

Are the punishments too harsh?

Schools often have a zero tolerance policy on drugs and thus students busted with drugs are more likely to be suspended or expelled. In a 2014 article The Sunshine Coast Daily reported that 40-69 students were suspended from government schools in 2013 for misconduct involving an illicit substance.

However the severity of such disciplinary action may lead to further disadvantage for the already vulnerable student.

In statements to The Age, drug and alcohol experts have raised concerns about schools’ decisions to expel students, warning that this punitive reaction may place the student at risk of social isolation and more substance abuse. Chief Executive of Youth Support and Advocacy Service, Andrew Brunn, stated that expelling students may cause them to ‘become disconnected from their school and their local community’, thereby putting the student at ‘risk of losing their sense of purpose and belonging.’ Moreover, Simon Biondo, chief executive of the Victorian Alcohol and Drug Association, held that expelling a student was a ‘short term’ solution. Alternatively, schools should offer students pastoral care before kicking them out as ‘expelling young people from school isn’t going to solve any of the school’s problems’.

These statements stand in contrast with the view of Judy Podbury, Australian Principals Federation’s Victorian president, who asserts that students that deliberately break school rules at special events like formals were opening themselves up for expulsion in order to make the school’s anti-drug message ‘clear and understood’. Nonetheless, Schools should realise the effect of expulsions on students.

In previous comments to the Sydney Morning Herald, NSW Education Minister Adrian Piccoli challenged the right of private schools to expel students, stating that ‘shifting the problem to another school is not the answer’. While no school is obliged to put up with ‘bad behaviour, abusing teachers or drugs in schools’, private schools should implement disciplinary procedures which ‘manage students properly’. Normally, students must be put through a period of suspension, counselling and extensive discussions with parents before Principals may even consider expulsion.

The extent to which expulsion is an effective means of addressing the drug problem in schools is a divisive issue. Students who leave a school may not have a place to go when help is needed and expulsion may only worsen the drug problem.

What programs can schools implement to reform young offenders?

Schools should implement rehabilitative programs as opposed to merely suspending or expelling students charged with the possession of illicit substances. In comments to ABC, Lisa Cuatt, president of Save the Children’s Youth Justice Program, states that it is unreasonable to expect young offenders to change immediately. Young offenders should be provided with one-on-one case management as suspensions/expulsions may only lead to social alienation and condemnation, thus causing students to emerge worse or more criminally motivated than to begin with.

Recently retired Tasmanian Chief Magistrate Michael Hill states that young offenders require strongly supported programs as they cannot “make it on their own”, particularly where negative social influences are so predominant. Schools can be safe and protected environments when proper programs are instituted in order to promote recreational and community engagement. Schools should foster a sense of belonging and purpose in the young offender, particularly as drug use is often motivated by family breakdown, poverty, bullying, abusive home lives and negative social pressures.

In NSW, School Liaison Police officers work in government high schools to reduce youth crime, violence and anti-social behaviour through education programs that foster relationships between students and teachers based on respect and responsibility. Some other school-based responses may be:

- Group counselling: Group students who are at the greatest risk of behavioural problems so as to provide guidance counselling in relation to personal problems or academic difficulties. This will reduce the student’s feeling of anonymity and increase student accountability, encouraging them to learn and abide by school rules and integrate into the school community;

- Parent-student conferences: Organise conferences which involve the participation of parents and offending students in order to identify the underlying causes of young offending. By addressing the core of the problem, teachers may reduce future drug incidents as well as other anti-social behaviours including vandalism, theft, fighting and truancy; and

- Mentor programs: Facilitate mentor programs where “at risk” youth may form relationships with pro-social peers and teachers within the school community.

These systems ensure that schools adopt a more sustainable approach to young offending. By promoting rehabilitation, schools reduce the risk of reoffending and foster a culture of acceptance. This can be contrasted to expulsion where schools merely make young offenders the problem of another community without addressing the underlying issues.

School Governance has written previous articles which outline the ways in which schools may strengthen their preventative drug and alcohol programs:

What next for schools?

School intervention can play a key role in ensuring that students do not enter the criminal justice system. Nonetheless, while schools may implement preventative programs, it is also important to ensure that a school’s response to confirmed drug incidents is fair and takes into consideration the bests interests of the child.

In circumstances of serious misbehaviour, a Principal may choose to expel a student of any age from their school. Nonetheless, this should only be done following consultation with a school counselor, who might instead present recommendations for alternative action. Principals should ensure that learning and support strategies have been tried before resorting to expulsion.

Does your school have rehabilitative programs for drug and alcohol offenders?

.png)